Persaud Lab

Energy Transition & Sustainability

EarthScope News Feature on "Monitoring microearthquakes of energy-storing salt domes in the Southeast US".

Link to our other research project in the US Gulf Coast: Southern Louisiana Micro-Seismicity (SOLAMS)

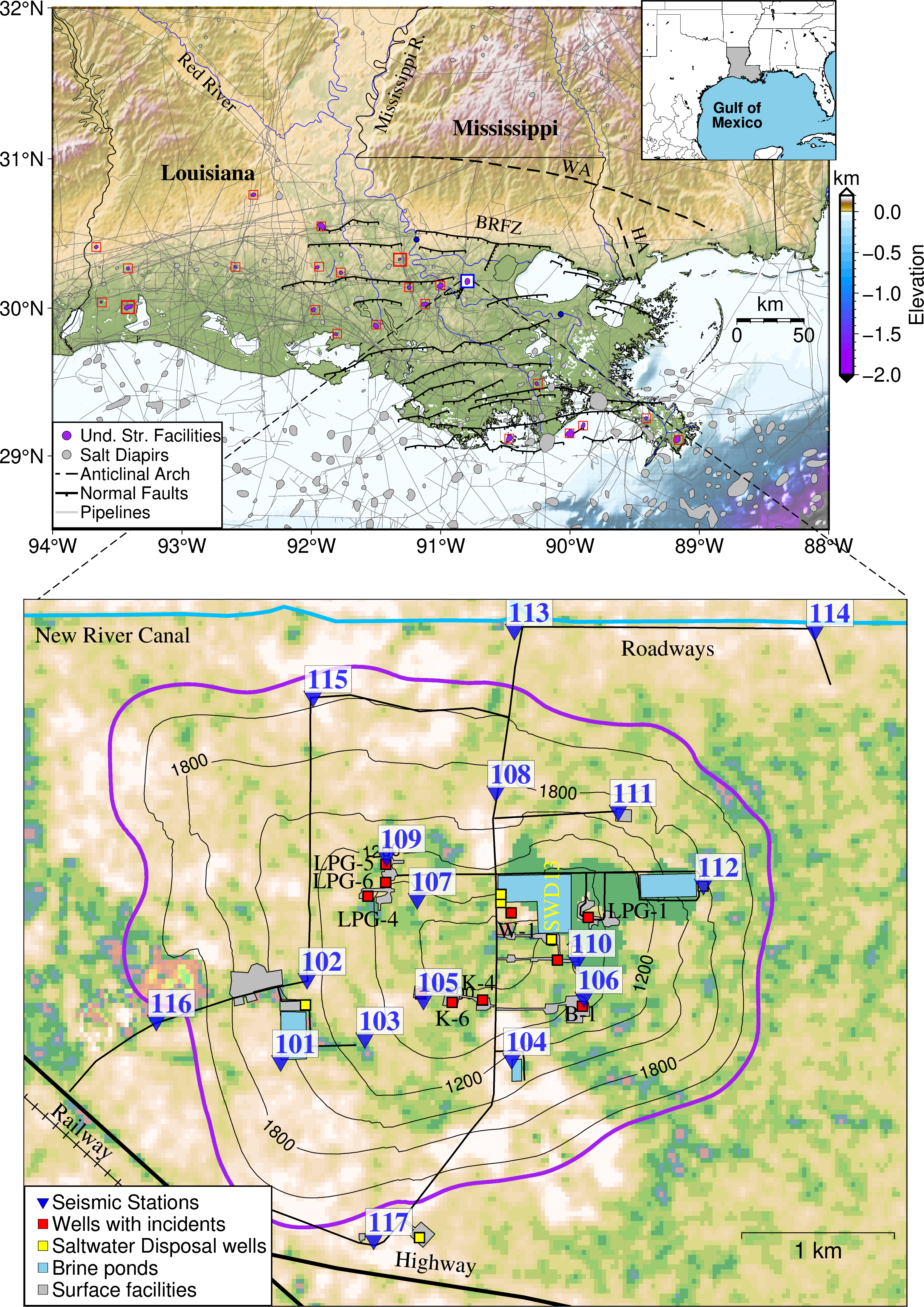

FIG. 1 Location map of the US Gulf Coast and Sorrento salt dome site in Louisiana. The lower map shows the positions of the 18 nodal stations installed in our study. The contours are depth to the salt diapirs caprock. Source: Omojola & Persaud (2024).

The global energy transition is accelerating the demand for stable, long-term underground storage facilities. Projects like the Advanced Clean Energy Storage (ACES) will enable the stockpiling of excess energy resources, effectively balancing the supply and demand of renewable energy. Typical underground storage options include depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs, aquifers, and salt caverns. Among these, salt caverns are often the most efficient due to their superior pumping cycles, lower operating costs, and high supply volumes (Omojola & Persaud, 2024; Liu et al., 2025). Their low permeability which enhances sealing potential, coupled with high recovery factors, make them ideal candidates for underground energy storage (Hou et al., 2024). While currently used primarily for hydrocarbons and liquified natural gas (LNG), these caverns are slated for future applications in compressed air energy storage and hydrogen as cleaner energy sources evolve.

While salt caverns are generally physically stable and "self-healing", impurities within the salt can jeopardize operations, increasing the risk of pipeline corrosion, casing failures, and cavern collapse. Geophysical characterization is therefore essential to evaluate storage integrity, both during the initial site selection and throughout continuous operations. In Omojola & Persaud (2024), we present a case study from southern Louisiana where geophysical monitoring combined with machine learning based methods helped identify infrastructure hazards impacting active storage operations.

The Sorrento salt dome located 70 km northwest of New Orleans, Louisiana (Figure 1), has an underground storage capacity of 8.92 bcf and has been used for hydrocarbon storage for over 30 years. Following reports of ground-shaking incidents in 2020, an array of nodal seismometers was deployed to monitor the site. To overcome high levels of industrial background noise that impeded signal identification, we developed a machine learning model to detect microearthquakes and built an earthquake catalog for the study area that covers a 1-year timeframe.

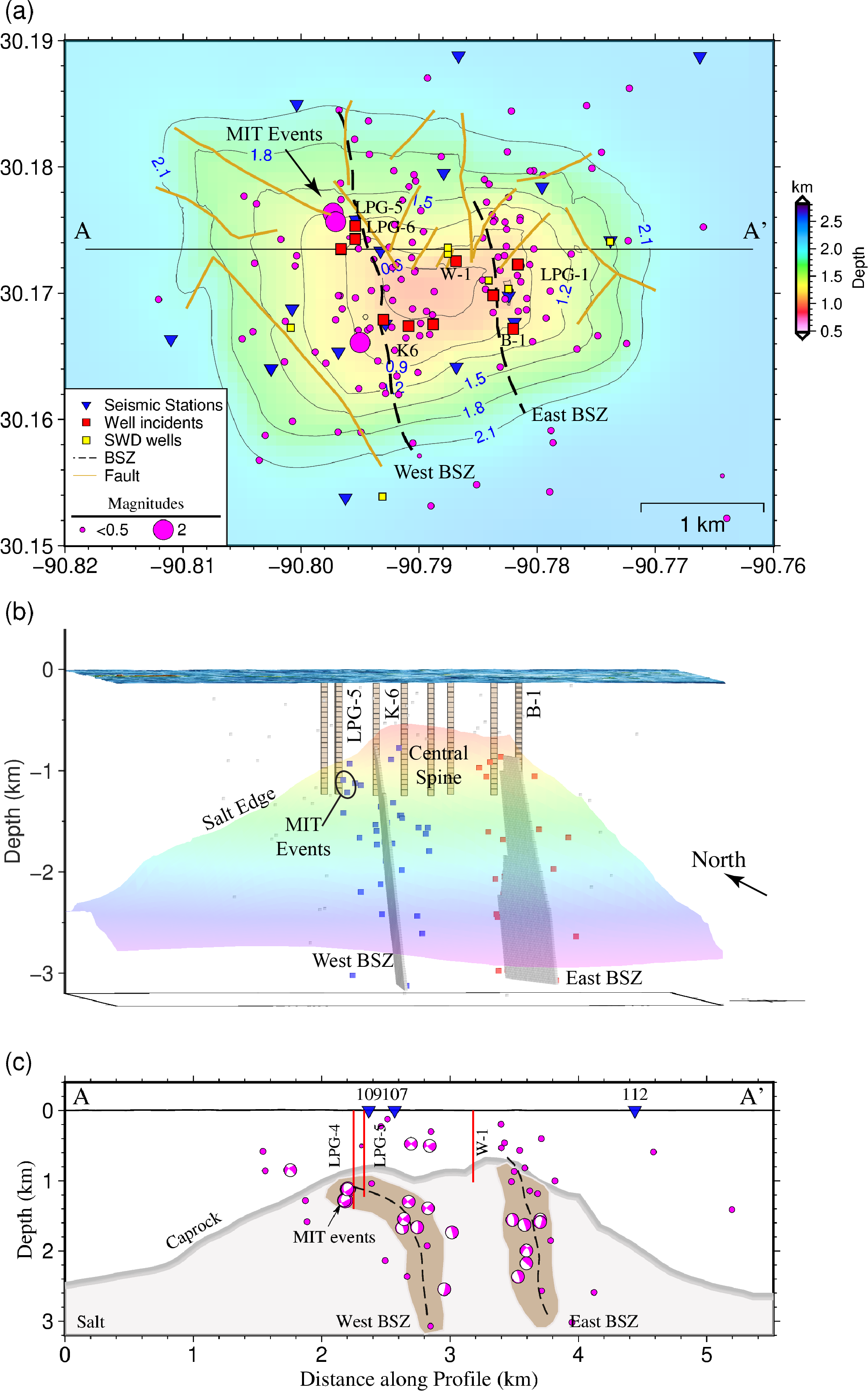

Our microearthquake locations were clustered along shear zones of weakness within the salt. We identified two shear zones (Figure 2) that were linked to repetitive well incidents including a mechanical integrity test failure that occurred in 2021. Using time-lapse sonar surveys, we tracked upward salt migration that was causing cavern deformation and highlighted stable portions of the salt for future cavern development.

This study demonstrates how geophysical characterization can identify seismic hazards at mature storage sites. It addresses important operational metrics, including cavern stability, leakage risk, and leachable capacity, providing a blueprint for safer energy storage in a carbon-neutral future.

FIG. 2 Map and 3D view of the shear zones within the salt dome. Brown lines on the top map are caprock faults. Seismicity used to define each shear zone, and impacted caverns are also shown. The central salt spine is best suited for future cavern development. Source: Omojola & Persaud (2024).

PUBLICATIONS (See Publications for meeting abstracts)

References

Hou, B., Shangguan, S., Niu, Y., Su, Y., Yu, C., Liu, X., … Zhao, K. (2024). Unique properties of rock salt and application of salt caverns on underground energy storage: a mini review. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, 46(1), 621–635.

Jianfeng Liu, Jianliang Pei, Jinbing Wei, Jianxiong Yang, and Huining Xu (2025). Development status and prospect of salt cavern energy storage technology. Earth Energy Science, Volume 1, Issue 2, Pages 159-179, ISSN 2950-1547.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the operators at the Sorrento salt dome in Ascension Parish, Louisiana, for providing access to the sites occupied by our seismic array. We are grateful to Justin Kain and Jeff Nunn for their help installing the instruments and to Jeff Hanor for discussions on the salt domes. We thank the USGS Lower Mississippi Gulf Water Science Center for releasing the preliminary data from the Bayou Conway station. Most computations were carried out on the LSU HPC SuperMike II cluster. Some of the seismic instruments were provided by the United States Geological Survey and Earthscope through the Earthscope Primary Instrument Center (EPIC) at New Mexico Tech. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant (2045983).

FIG. 3 Installation of a nodal seismic station by the project team at the Sorrento Salt Dome, Louisiana in 2020.